Feeding and Eating after PICU

The PICU is a disruptive time for infant, child, and adolescent eating and feeding. There are range of causes for this, such as unpleasant or painful oral medical interventions such as endotracheal tubes (ETT), extubations and re-intubations, nasogastric tube (NGT) insertion and frequent oral suctioning (1) which may cause feeding and eating to be painful. Additionally, environmental factors in PICU such as unnatural lighting (from overhead lights and machines) and noise disruptions (from machines and from other people talking or making noise in the unit) as well as sedation medication can disrupt usual routines which may in turn cause challenges when returning home from PICU.

Because many skills (from sucking and swallowing to social interaction skills) and benefits (such as comfort and enjoyment) are developed and gained from feeding and eating, the disruptions to feeding and eating in PICU may cause delays or problems not only in feeding and eating but also in a range of developmental, emotional, and other domains (read more here).

PICU Dietitians, Speech Pathologists, Occupational Therapists and other professionals can help your child as they wean from NGT or IV nutrition to oral feeding or to home-based NGT.

Infants and babies (0-2 years)

Feeding for babies and infants is not only for nutrition, but also for comfort (sucking, smell, and caregiver touch), sensory input (sucking and flavour) and social interaction (shared mealtimes and communication). It is possible to replicate or supplement some of these benefits of feeding while your child is still in the PICU, and ways to help get back on track with these skills when returning home.

Some ways that you can provide the benefits of feeding to your child while in PICU are:

If breastfeeding, place your used breastpads near your baby so that they can be soothed and comforted by your smell. Even if you are not breastfeeding, you can still use a pad or piece of fabric to leave your smell with your baby (talk to your nurse to see what would be most appropriate and hygienic in the PICU).

If expressing breastmilk, you can speak to your nurse or PICU speech pathologist about dipping pacifiers in your breastmilk to introduce the flavour (if appropriate with your child’s current feeding interventions).

Comfort and physical touch even while your child is asleep or sedated has a range of benefits from assisting pain management to improved sleep and outcomes (read more here).

After PICU, you may need help from a lactation consultant, dietitian, speech pathologist, or other health professionals to help you achieve feeding goals that work for you and your child. See your GP for a referral or for more help, or call 1800 686 268 to speak to a lactation consultant for free. There is also a free lactation consultant online chat available here. Unfortunately, the cost of face-to-face lactation consultant appointments are not free in Australia (some may have a partial medicare rebate). Speak to your lactation consultant clinic before your appointment for specific information on fees and any rebates oferred.

More resources and information:

Maintaining Your Milk Supply While Baby Is Hospitalized

Australian Breastfeeding Association Resources

Lactation Consultants of Australia and New Zealand Resources (and find a lactation consultant near you)

Instagram Pages for Information:

@nourished.babes - Jamie Williams is a paediatric speech pathologist who posts tips for supporting

parents in nourishing their babe’s communication and feeding through a relationship centred approach.

@nourishingbubs - Helping Parents Raise Healthy Children.

Toddlers (2-4 years)

Feeding and eating for toddlers is not only for nutrition, but also play and behavioural and social skills, and for learning physical skills such as tongue movement and swallowing. Children of this age may develop aversions to eating, changes to appetite, and feeding and eating routines after PICU. This may be due to a number of causes such as an extended period of time on NGT, disrupted routines or wakefulness while in PICU due to medications and environmental disruptions (read more here), and/or due to emotional and social problems or challenges due to the illness/injury and hospital admission itself (read more here).

Children who had an extended period of tube or parenteral feeding (>7 days):

Children who have had feeding interventions (such as NGT or parenteral nutrition) for an extended period of time may have challenges transitioning to oral feeding, such as changes to appetite when returning home due to extended periods of not “needing” an appetite in PICU due to continuous tube feeds. This understandably is a big transition to make back to having a chance to become hungry between feeds, and to experiencing the flavours and feeling of having a full stomach after eating, which may initially cause some abdominal discomfort. Other children may be fearful or anxiousof having anything put near their mouth due to memories or painful procedures of tubes being inserted in their mouth.

What to know about transitioning from an extended period of tube/parenteral feeding to oral:

A speech pathologist, dietitian, and/or other health professionals is necessary to provide assessment and a plan for this transition.

The health professional will help to make sure that your child has the necessary motivations to eat (hunger, flavour, and safe/known foods).

The health professional will help make sure your child has the necessary skills to feed or eat (tongue movements, swallowing).

You may also want to consider the emotional and behavioural challenges your child may face due to an extended PICU stay which can impact feeding/eating (read more here).

Children who had a short PICU stay or short period of tube or parenteral feeding (<7 days):

Social, emotional, physical, cognitive (thinking), and family factors all affect the recovery after PICU (read more here). It is important to consider these factors and any fears your child may have developed from the illness/injury and the PICU admission itself. Many parents and caregivers of children with a short (<7 days) PICU stay often go home without additional feeding support to manage their child’s recovery. However, considering the growing myriad of challenges after PICU, this can be challenging for families and their children, and frustrating if you don’t have the additional resources and support needed for this transition. We recommend seeking help from your GP for referral to a dietitian or speech pathologist to help get you started and to manage your child’s recovery if required. You may also wish to call a free child health nurse on 13 43 25 84 (ask for child health nurse) or Parentline on 1300 30 1300 if you have any questions and would like some immediate advice.

What to know about re-introducing (or introducing) oral feeding and eating after PICU for children after a short stay:

Research shows that eating together at mealtimes with your child (even if just with one caregiver) can provide the social benefits of eating for infants and young children.

Eating without screens on (e.g. TV, phones) helps children and adults to be mindful of their satiation (feeling of “fullness” after eating) and the flavours and textures of food they are eating. This is also helpful for improving mindfulness and awareness and reducing feelings of depression and anxiety.

You may wish to try sensory food play to encourage playfulness, exploring, and enjoyment with foods prior to mealtimes. You don’t have to put in too much effort, even playing with broccili flora as “little trees” on some mashed potato “dirt” can help encourage play and fun with food. This can be done during the day outside of set meal times so that there is less pressure at meal times to see and taste the new foods for the first time.

Offer new foods alongside a preferred/favoured food so that infants and children can safely explore new flavours and textures knowing that there is a safe alternative to eat.

Avoid bribing or using food as a reward, and avoid offering food at all times of the day.

More resources and information:

Toddlers at the Table: Avoiding Power Struggles

Fussy Eating Tips (Monash Children’s Hospital)

Child Health Nurse Phone (free) 13 43 25 84

Parentline Website and phone (free) 1300 30 1300

Children (4-12 years)

As children reach pre-school and school age, mealtimes continue to serve not only for nutrition and energy but also for social and behavioural skills development. Habits formed in this period of life can help develop healthy eating habits for life. PICU disrupts a number of health domains such as cognitive (thinking), emotional wellbeing, social and physical functioning, and family wellbeing (read more here). Developing a healthy diet is known to offer positive benefits for all of these domains.

Despite these benefits, barriers such as the time and distance it takes to get to fresh food markets or supermarkets, time for cooking, and higher costs of healthier foods make it harder, not easier, for families to eat healthy food for every meal. Below are some tips that aim to help make it easier, not harder, for you to achieve a healthy diet.

Tips for food preparation, eating, and enjoying food for you and your child:

Research shows that eating together at mealtimes with your child (even if just with one caregiver) can provide the social benefits of eating for infants and young children.

Eating without screens on (e.g. TV, phones) helps children and adults to be mindful of their satiation (feeling of “fullness” after eating) and the flavours and textures of food they are eating. This is also helpful for improving mindfulness and awareness and reducing feelings of depression and anxiety.

Consider a food delivery service or “click and collect” options at your local supermarket to save time and effort shopping.

Look at “ugly foods” or “imperfect picks” fruits and vegetables in your supermarket, which are cheaper due to aesthetic imperfections (with no impact on taste or nutritional content!). There are also delivery imperfect foods such as Funky Foods starting from $25 per delivery (funky food Australia), or search for local imperfect food options in your area.

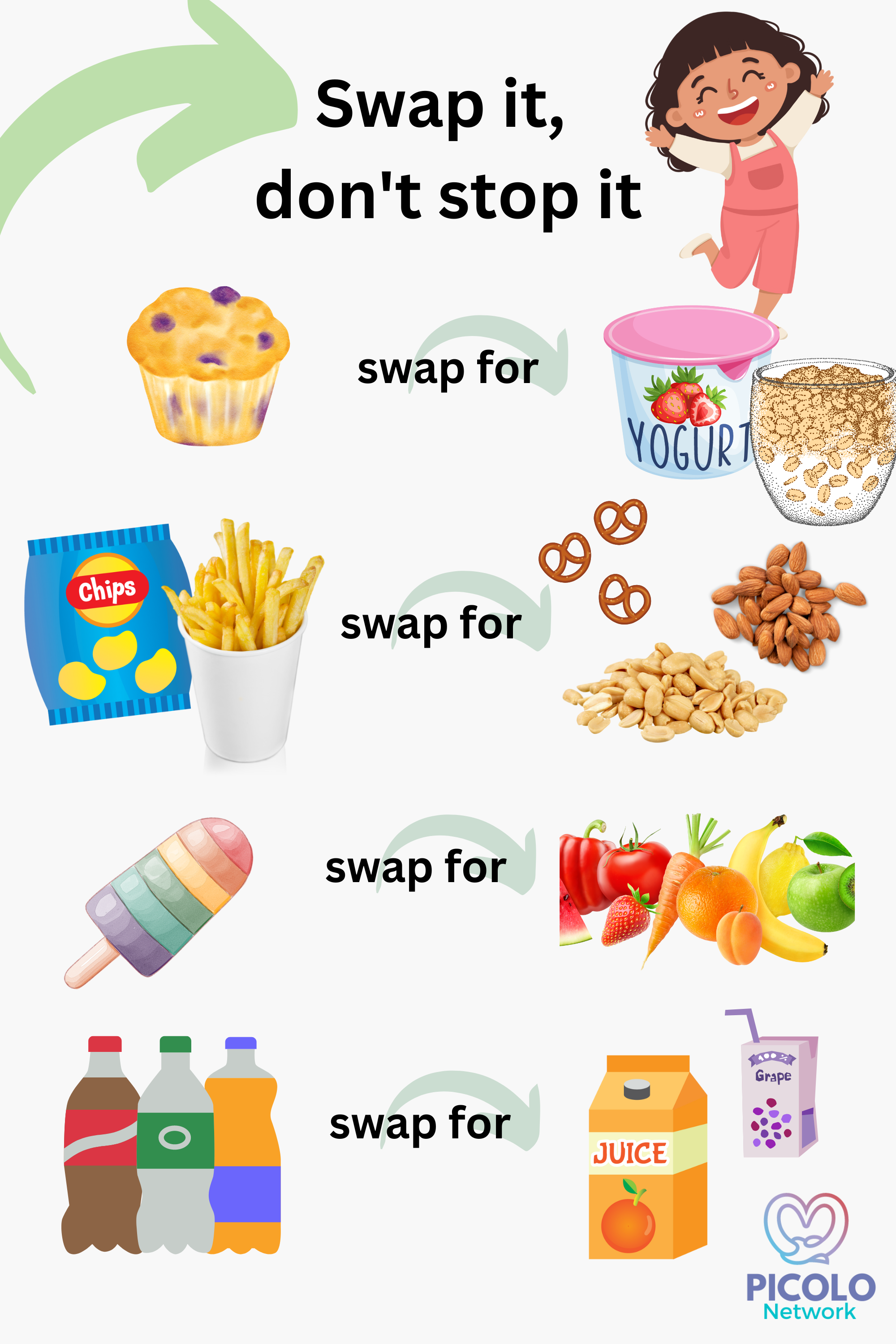

It’s very difficult to change your eating habits by trying to stop eating a food altogether, especially if your hunger or taste desires aren’t met. It is much easier to swap out an unhealthy food for a similar but healthier food option that you enjoy. Visit the “Swap It” (don’t stop it) website for easy tips on everyday lunchbox foods (video below).

To set yourself up for a win to avoid hunger and buying quick (and often expensive) convenience foods when out, stock up on some healthy, non-perishable snacks for your pantry, car, handbag, and work desk. These could include popcorn, granola, peanut butter, pretzels, unsalted almonds or peanuts, dried chickpeas, rice cakes, or canned tuna and microwave rice. Pick foods that you actually enjoy eating.

Start involving your child in food preparation to encourage responsibility, sharing, turn-taking, and physical skills. You could start small with the job of washing fruit and vegetables, getting things from the fridge, or stirring. Raising Children Network have some tips on how to involve your child (of any age) in food preparation.

Alongside food preparation with your child, allow snacking on food while preparing meals, such as cut-up vegetables like carrot or cucumber. This way, if less vegetables are consumed at meal times, you can feel more comfortable knowing that your child has consumed some vegetables. This may also help meal times feel less pressured and have less negotiation or power struggles with your child.

More resources and information:

Raising Children Network - Cooking with Children and Teenagers

Fussy Eating Tips (Monash Children’s Hospital)

Swap it, don’t stop it video (source: https://www.swapit.net.au/)

Teenagers/Adolescents (12-18 years)

After going home from PICU, teenagers may have reduced muscle tone or physical abilities due to an extended illness or PICU stay, yet may have reduced or altered appetite, impacted sleep and other usual cognitive (thinking) tasks, physical activities, and impacted social and emotional wellbeing (read more here) impacting their recovery. In the 48-72 hours after PICU, up to 50% of teenagers can experience mild, moderate, or severe anxiety, however this can diminish to below clinical thresholds after one month at home (5). This means that the first few days or weeks after PICU may the hardest for your child adjusting back home, but it can get better over time. Some problems can be consistent or worsen over time, and it is important to identify these as early as possible with a suitable healthcare provider.

Supporting teenagers after PICU may involve empowering them to discuss and set some of their own goals and aims for recovery, for example being able to participate in sports or social activities at school or outside-of-school groups. Teenagers often have their own ideas of what they would like to achieve, and sharing these with their healthcare provider and family can provide them with the support needed to achieve them. Research has also found that self-efficacy, or the belief in one’s own abilities to achieve set goals, is important in achieving those goals after PICU for teenagers (6). Therefore, encouraging your teenagers that they are able to achieve their goals is an important component of their recovery.

Currently, there is no PICU follow-up offered in Australia (outside of specific patient cohorts such as cardiac or oncology patients) to provide early screening for problems, therefore it is important to be mindful of challenges that often occur after PICU, and to seek help from your GP or healthcare provider to help manage recovery.

The work that PICOLO Network is currently undertaking research that aims to collect more information on child and adolescent outcomes after PICU and to develop follow-up in order to improve recoveries after PICU.

More resources and information:

References:

Rennick JE, Johnston CC, Dougherty G, et al. Children's psychological responses after critical illness and exposure to invasive technology. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2002;23:133–44.doi:10.1097/00004703-200206000-00002pmid:http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12055495

Senez C, Guys JM, Mancini J, et al. Weaning children from tube to oral feeding. Childs Nerv Syst 1996;12:590–4.doi:10.1007/BF00261653pmid:http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8934018

Dello Strologo L, Principato F, Sinibaldi D, et al. Feeding dysfunction in infants with severe chronic renal failure after long-term nasogastric tube feeding. Pediatr Nephrol 1997;11:84–6.doi:10.1007/s004670050239pmid:http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9035180

Mehta NM, Skillman HE, Irving SY, et al. Guidelines for the provision and assessment of nutrition support therapy in the pediatric critically ill patient: Society of critical care medicine and American Society for parenteral and enteral nutrition. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2017;18:675–715.doi:10.1097/PCC.0000000000001134

Bichard, E, Wray, J, Aitken, LM. Discharged from paediatric intensive care: A mixed methods study of teenager's anxiety levels and experiences after paediatric intensive care unit discharge. Nurs Crit Care. 2022; 27(3): 429-439. https://doi.org/10.1111/nicc.12703

Azevedo R, Rosário P, Martins J, Rosendo D, Fernández P, Núñez JC, Magalhães P. From the Hospital Bed to the Laptop at Home: Effects of a Blended Self-Regulated Learning Intervention. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(23):4802. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16234802